Now that Opportunity’s mission is complete, many wistfully lament about “bringing our robot home.” There’s just one problem: it’s already home.

I am fascinated with how we anthropomorphize robots, particularly space robots. We call them “brave,” “pioneers” and even give them genders — usually a “she.” We get emotional when they reach the end of their missions, saying they’ve “died” or, as I like to say, “gone to Silicon Heaven.” But these robots are, for all intents and purposes, tools. Sure, they expand the reach of our senses, allowing us to see strange new worlds and parts of the universe where humans fear to tread, but they’re an assembly of electronics, metal, plastic, sensors, transmitters, wheels and solar panels. They don’t have emotions. They don’t breathe. They don’t philosophize about the incredible feats of exploration they are undertaking. They don’t have genders.

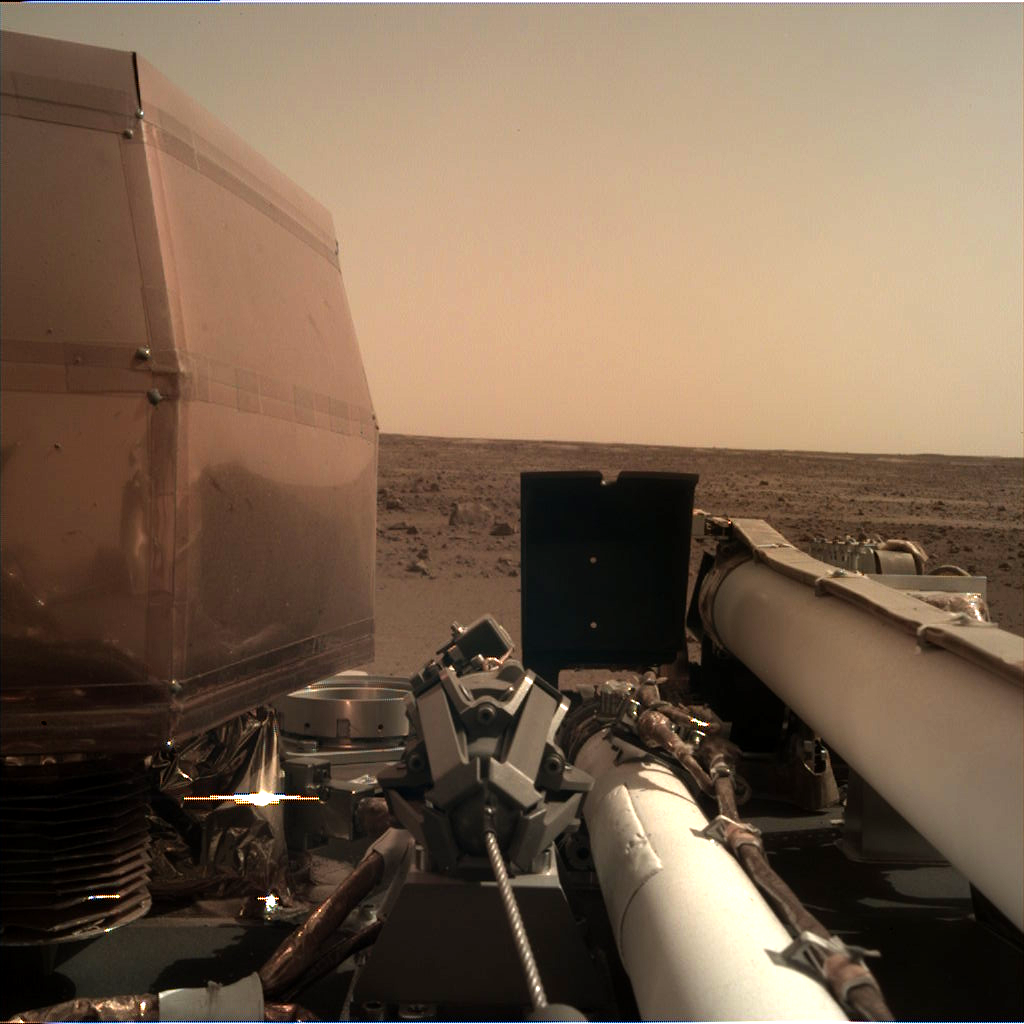

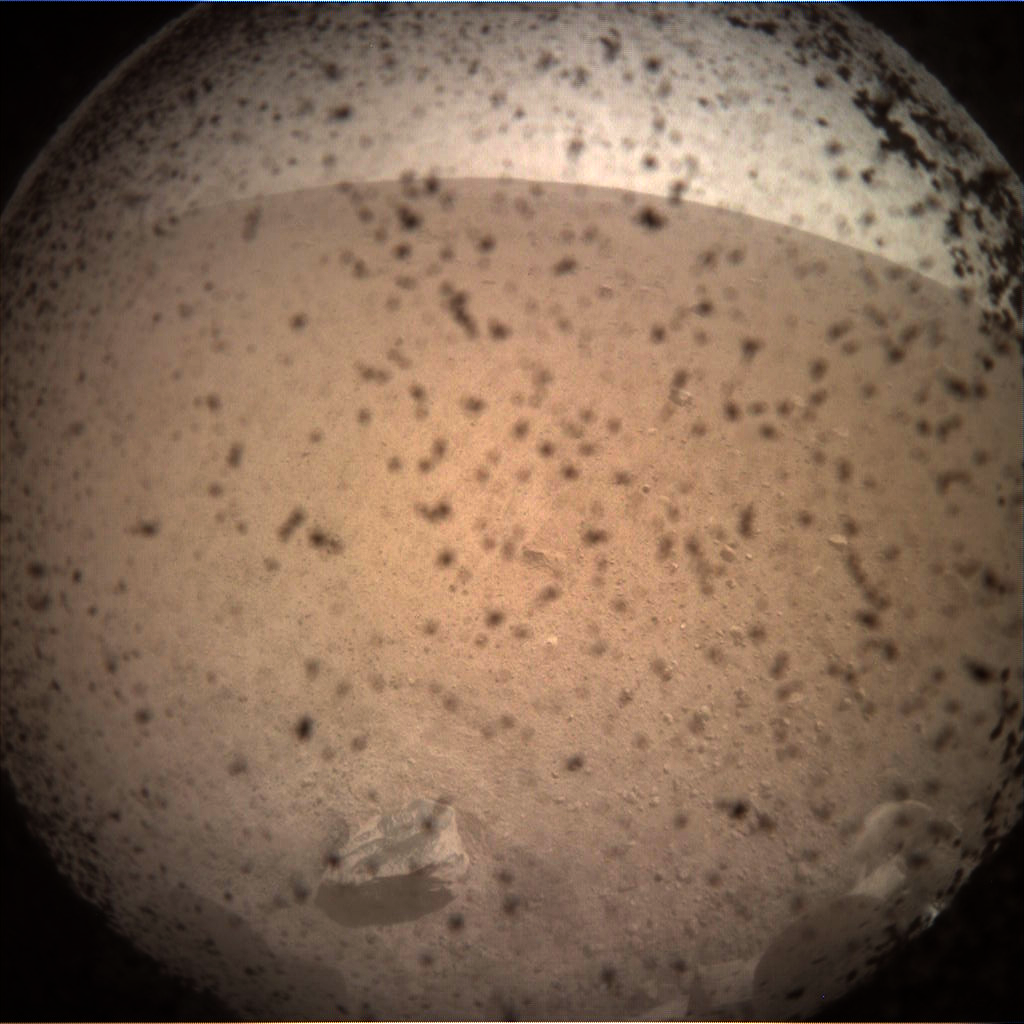

Still, we fall in love. When watching Curiosity land on Mars from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, I teared up, full of joy that the six-wheeled hulk of a rover — that I’d met personally in JPL’s clean room a couple of years before — had safely landed on the Red Planet. After watching NASA’s InSight lander touch down on Elysium Planitia, again via JPL’s media room last year, there it was again, I was in love. I’m already anthropomorphizing the heck out of that mission, seeing InSight’s landing as another “heartbeat” on Mars. When the European Rosetta mission found Philae lying on its side like a discarded child’s toy on the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, I jumped up from my desk with joy. When Cassini’s mission at Saturn ended in 2017, I was miserable. When the Chinese rover Yutu rolled off its lander in 2014, I realized I was cheering the robot on. When Spirit got stuck in a sand trap in Gusev Crater, I set up a Google alert for any and all news on the recovery efforts.

These emotions aren’t just for the exciting science and engineering strides humanity makes, there’s a certain inspirational character that each robot brings. Undoubtedly, this character naturally emerges from the wonderful scientists and engineers who design and build these amazing machines, and the social media managers who often “speak” for their robots in first person. But if you strip away the science, the technology and the people who build them, we still personalize our beloved robots, giving them their own character and creating a cartoon personality. I believe that’s a beautiful trait in the human condition (except a few flawed cultural and stereotypical missteps) and can be used to great effect to captivate the general public with the science that these robots do.

So there’s no great surprise about the outpouring of emotion for last week’s announcement that NASA called off the communications efforts with Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity. This kick-ass robot traveled 28 miles and lasted nearly 15 years, until a global dust storm in early 2018 starved it of sunlight. It landed on Mars way back in 2004, with its twin, Spirit, beginning its Martian reign with a hole-in-one, literally — after bouncing and rolling across the regolith after its entry and descent, encased inside a genius airbag system, it plopped inside the tiny Eagle crater. We’ve collectively lived through Opportunity’s adventures and the groundbreaking science it has done. There’s a huge number of terrific robot obituaries out there, so I won’t duplicate those efforts here. There is, however, a recurring sentiment that is somewhat misplaced, though entirely innocent.

Opportunity — like Spirit and all the Mars rovers and landers that have come and gone — died at home.

This may sound like an odd statement, but there seems to be this fascination with “returning” our space robots to Earth. I’ve seen cartoons of the Dr Who traveling through time to “rescue” Opportunity. People have argued for the case of future Mars astronauts returning these artifacts to terrestrial museums. There’s that touching XKCD cartoon of Spirit being “stranded” on Mars after NASA declared it lost in 2010, that is being resurfaced for Opportunity. We want our dusty Mars rover back!

It’s understandable, that rover has been continuously exploring Mars for a decade and a half, many of its fans, including myself, could check in on Opportunity’s adventures daily, browsing the latest batch of raw images that were uploaded to the NASA servers. We love that thing. In the tradition of military service members who die abroad, we go to great efforts to bring their bodies home so they can repatriated; we want to repatriate our science service member back to Earth.

But Opportunity is a robot that was designed for Mars. Every single design consideration took the Martian environment into account. The Red Planet’s gravity is roughly 1/3rd that of Earth, so the weight on its actuators and chassis are 2/3rds less than what they’d experience on our planet. Its motors are too under powered to reliably drive the robot forward on Earth. On Mars, they’re perfect. Granted, the mass of the Mars Exploration Rovers (approximately 185 kg) are a lot less than their supersized cousin, Curiosity (899 kg), but if Opportunity and Spirit had a 90-day mission exploring the dunes of the Californian Mojave Desert, I’m betting they wouldn’t get very far; they would be under-powered and grind to a halt. They’d also likely overheat as they were designed to withstand the incredibly low temperatures on the Martian surface.

The robots we send to Mars are undeniably Martian. If we’re going to anthropomorphize these beautiful machines, let’s think about what they’d want. I’m guessing they’d want to stay on that dusty terrain and not return to the alien place where they were constructed. And, in doing so, they become the first generation of archaeological sites on the Red Planet that, one day, the first biological Martians will visit.