For the festive season, our nearest star is keeping its choice of costume simple.

I’m not saying the Sun isn’t being creative, it’s just not putting too much effort into this year’s stellar fancy dress party. I mean, look at it:

That flawless orange billiard ball is the photosphere of our Sun. Have you ever seen something so smooth and beautifully unremarkable?

Well, you have now, and its blank gaze is actually the reason why it’s causing a bit of a stir. According to our ever watchful solar sentry, Tony Phillips at SpaceWeather.com, the northern summer of 2019 may go down in history as “the summer without sunspots.”

From June 21st until Sept 22nd, the sun was blank more than 89% of the time. During the entire season only 6 tiny sunspots briefly appeared, often fading so quickly that readers would complain to Spaceweather.com, “you’ve labeled a sunspot that doesn’t exist!” (No, it just disappeared.) Not a single significant solar flare was detected during this period of extreme quiet.

Dr. Tony Phillips

So, what does this mean?

Sunspots are the visual cues for magnetic turmoil within our nearest star. Over cycles of approximately 11 years, the Sun’s internal magnetic field becomes stretched and twisted, driving the ebb and flow of space weather.

Starting with our solar billiard ball here, suffice to say that the solar magnetic field is pretty untwisted and, well, chilled. This is the epitome of “solar minimum” — and, as commented on by Phillips, a deep, potentially record-breaking solar minimum at that. It’s very likely that this is as minimum as solar minimum can be, so we could hazard a guess to say that things are going to start getting interesting very soon.

As our Sun is a massive blob of magnetized plasma, it doesn’t rotate uniformly (like the Earth does), it actually rotates a little faster at its equator than at its poles, a phenomenon known as “differential rotation.” Now, if you imagine the solar magnetic field as straight lines running from pole to pole, you can imagine that, over time, the field will start to wrap around the equator like an elastic band being stretched out of shape and wrapped around the middle. At its most extreme, so much rotational tension will be applied to the magnetic field that it becomes contorted. This contortion creates an upward pressure, forcing vast loops of magnetized plasma, known as coronal loops, to pop through the Sun’s photosphere — a.k.a. the solar “surface” — like annoyingly twisted loops of garden hosepipe (see the diagram above).

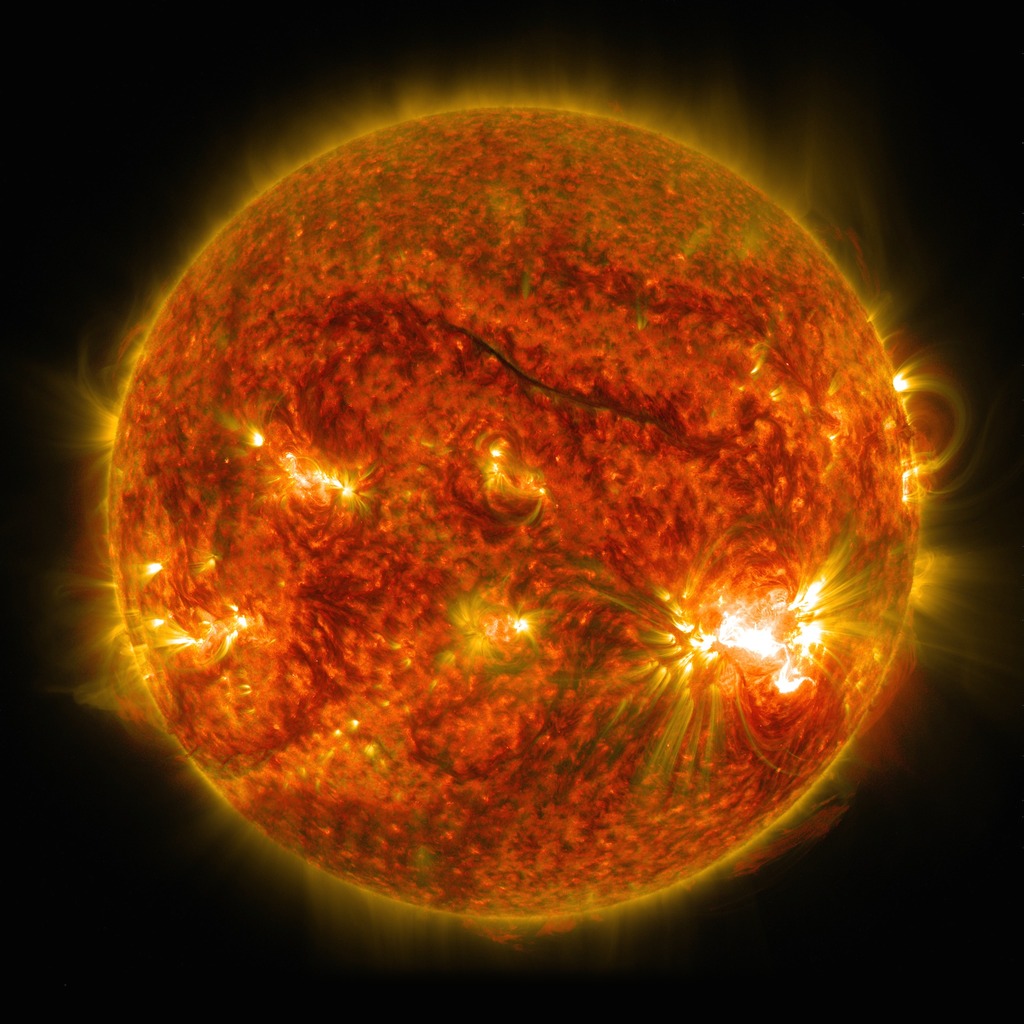

As its most extreme, in a few years time, we can expect our boring ol’ billiard ball to look something like this:

About those blotches: those dark spots are sunspots and they are a direct consequence of the magnetic turmoil that rumbles inside the Sun during solar maximum. Remember those coronal loops I was talking about? Well, these huge, beautiful arcs of plasma cause the hotter outer layers of the Sun to be pushed aside, exposing the comparatively cooler (though still thousands of degrees) plasma under the surface — that’s what creates those dark blotches. And by counting sunspots, you can gauge how magnetically active the Sun is.

By viewing the Sun in different wavelengths, we can view the Sun’s atmosphere at different temperatures and, as the Sun’s atmosphere (the corona) is counter-intuitively hotter the higher above the surface you get, let’s take a look at what solar maximum looks like above these sunspots:

As you can see, there’s a lot of coronal loops erupting through the surface, creating huge regions of activity (called active regions, unsurprisingly). And the above observation was captured on Oct. 8, 2014, when the Sun was, apparently, in a terrifyingly festive Halloween mood! These regions can be hothouses for solar flares and coronal mass ejections; explosive phenomena that can have dramatic space weather effects on Earth.

So that was solar maximum; what does the solar corona look like now, at solar minimum?

Yep, as you guessed, very relaxed. In this state, we can expect very little in the way of explosive space weather events, such as flares and CMEs; there’s simply too little magnetic energy at solar minimum to create many surprises (caveat: even solar minimum can generate flares, they’re just few and far between).

While the Sun may look boring, the effects of space weather are anything but. During these times of solar minimum, the extended solar magnetic field (called the heliosphere), a magnetic bubble that reaches beyond the orbits of all the planets, contracts and weakens, allowing more cosmic rays from energetic events from the rest of the cosmos to reach Earth. Cosmic rays are ionizing particles that can boost the radiation exposure of astronauts and frequent fliers. Also, the solar wind can become a more persistent presence; streams of energized particles that are continuously streaming from the lower corona, so we still get our aurorae at high latitudes.

Recognition that the Sun is now in a deep minimum means the solar vacation is nearing an end. Astronomers have reported that of the handful of sunspots have made an appearance over the last few months with a flip in magnetic polarity, which can mean only one thing: Solar Cycle 25 is coming and the next solar maximum is only four years away.