Scientists are closing in on a better understanding about how these magnetic eruptions evolve

For the first time, scientists have created a computer model that can simulate the evolution of a solar flare, from thousands of miles below the photosphere to the eruption itself in the lower corona — the sun’s multimillion degree atmosphere. And the results are not only scientifically impressive, the visualization is gorgeous.

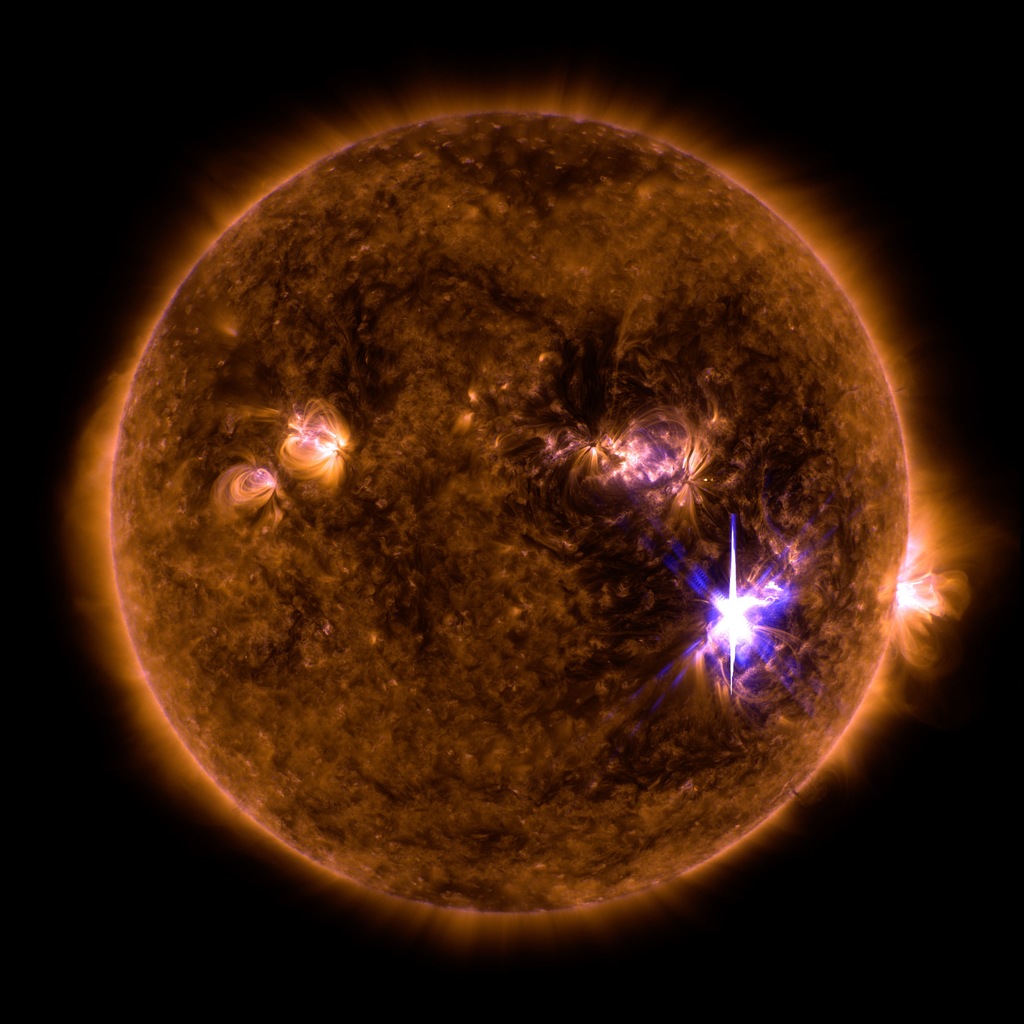

I’ve always had a fascination with the sun — from how our nearest star generates its energy via fusion reactions in its core, to how the tumultuous streams of energetic plasma slams into our planet’s magnetosphere, igniting spectacular aurorae. Much of my interest, however, has focused on the lower corona; a region where the intense magnetic field emerges from the solar interior and reaches into space. With these magnetic fields comes a huge release of hot plasma that is channeled by the magnetism to form beautiful coronal loops. Intense regions of magnetism can accumulate in violently-churning “active regions,” creating sunspots and explosive events — triggered by large-scale magnetic reconnection — such as flares and coronal mass ejections (or CMEs). This is truly a mysterious place and solar physicists have tried to understand its underlying dynamics for decades.

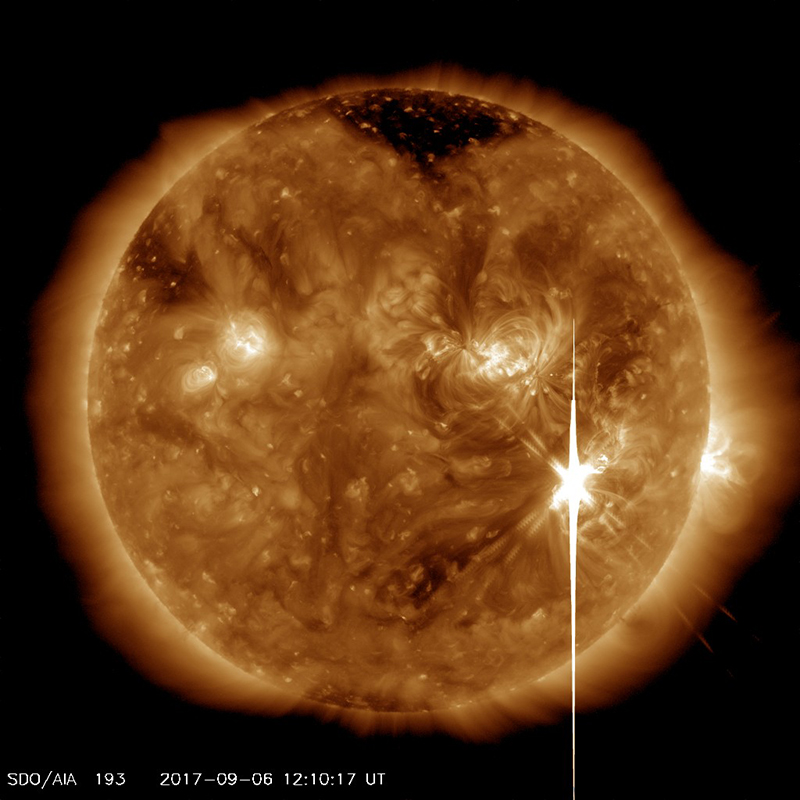

Now, with increasingly-sophisticated solar observatories (such as NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory), we are getting an ever more detailed look at what’s going on inside the sun’s deep atmosphere and, with improvements of theoretical models and increases in computer processing power, simulations of the corona are looking more and more like the real thing. And this simulation, detailed in the journal Nature Astronomy, is truly astonishing.

In the research, led by researchers at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and the Lockheed Martin Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory, the evolution of a solar flare has been modeled. This simulation goes beyond previous efforts as it is more realistic and creates a more complete picture of the range of emissions that can be generated when a solar flare is unleashed.

One of the biggest questions hanging over solar (and indeed, stellar) physics is how the sun (and other stars) heat the corona. As we all know, the sun is very hot but its corona is too hot; the photosphere is a few thousand degrees, whereas, only just above it, the coronal plasma skyrockets to millions of degrees, generating powerful radiation beyond what the human eye can see, such as extreme-ultraviolet and X-rays. Basic thermodynamics says that this shouldn’t be possible — this situation is analogous to finding the air surrounding a light bulb is hotter than the bulb’s glass. But what our sun has that a light bulb does not is a powerful magnetic field that dictates the size, shape, temperature and dynamics of the plasma our sun is blasting into space. (If you want some light reading on the subject, you can read my PhD thesis on the topic.)

“This work allows us to provide an explanation for why flares look like the way they do, not just at a single wavelength, but in visible wavelengths, in ultraviolet and extreme ultraviolet wavelengths, and in X-rays. We are explaining the many colors of solar flares.”

Mark Cheung, staff physicist at Lockheed Martin Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory.

The basis of this new simulation, however, investigates another mystery: How and why do solar flares erupt and evolve? It looks like the research team might be on the right track.

Inspired by a powerful flare that was observed in the corona in March 2014, the researchers provided their magnetohydrodynamic model with an approximation of the conditions that were observed at the time. The magnetic conditions surrounding the active region were primed to generate a powerful X-class flare (the most powerful type of solar flare) and several less powerful (but no less significant) M-class flares. So, rather than forcing their simulation to generate flares, they re-enacted the conditions of the sun that were observed and just let their simulation run to create its own flares.

“Our model was able to capture the entire process, from the buildup of energy to emergence at the surface to rising into the corona, energizing the corona, and then getting to the point when the energy is released in a solar flare,” said NCAR scientist Matthias Rempel in a statement. “This was a stand-alone simulation that was inspired by observed data.

“The next step is to directly input observed data into the model and let it drive what’s happening. It’s an important way to validate the model, and the model can also help us better understand what it is we’re observing on the sun.”

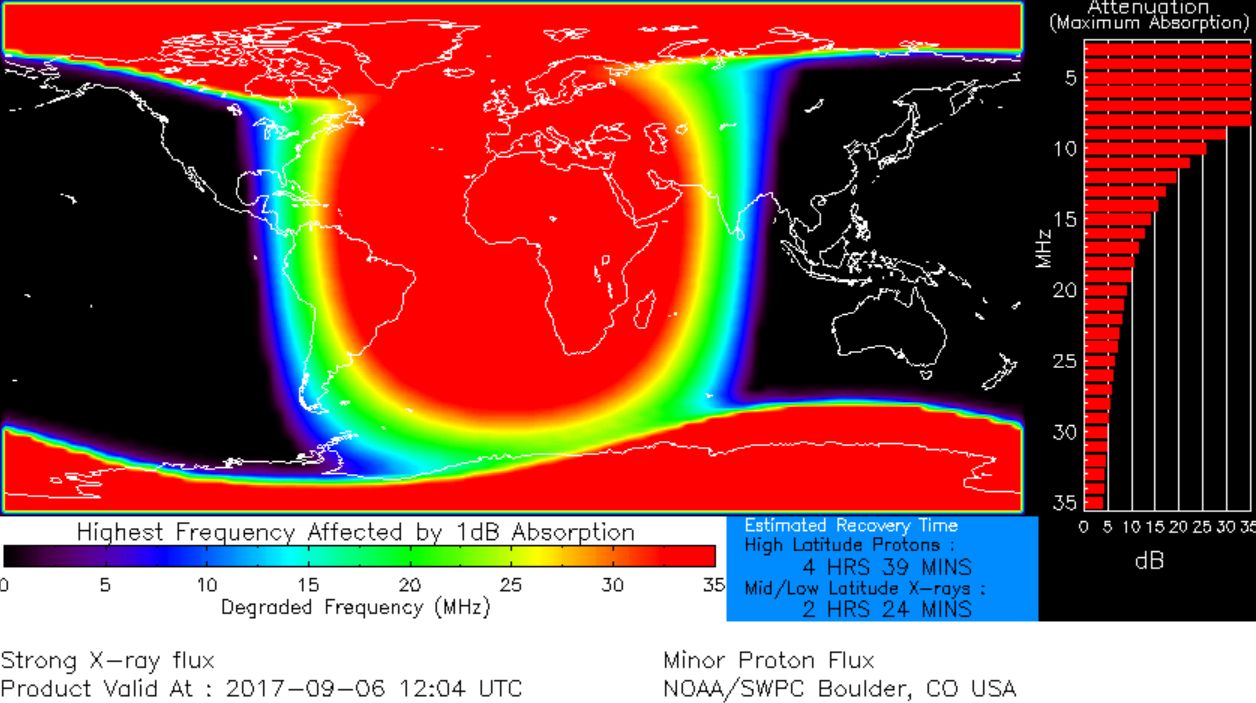

Solar flares, CMEs and even the solar wind can have huge impacts on our technological society. The X-rays blasting from the sun’s atmosphere millions of miles away can have dramatic impacts on the Earth’s ionosphere (impacting communications) and can irradiate unprotected astronauts in space, for example. CMEs can be launched from the corona and arrive at Earth orbit in a matter of hours or days, triggering geomagnetic storms that can impact entire power grids. We’re not just talking a few glitches on your cellphone here; satellites can be knocked out, power supplies neutralized and global communications networks interrupted. It’s simulations like these, which aim to get to the bottom of how these solar storms are initiated, that can help us better prepare for our sun’s next big temper tantrum.

For more on this research, watch this video: