The space telescope has refined the stellar flybys of the Voyager and Pioneer probes—how might it help us chart our way to the stars in the future?

When looking up on a starry night, it can be difficult to comprehend that those stars are not fixed in the sky. Sure, on timescales of a human lifetime, or even the entirety of human history, the stars don’t appear to move too much. But look over longer timescales—tens of thousands, to millions of years—and it becomes clear that the stars in the sky are in motion. This means the constellations we see today will be misshapen (or even non-existent!) in a few hundred thousand years’ time.

This poses an interesting question: If humanity were to send a spacecraft on an interstellar mission—an endeavor that could take thousands of years, depending on how ambitious the target—aiming it directly at a distant star would be a mistake. Depending on how far away that star is, by the time the spacecraft reaches its target, the star could have moved a few light-years away. This is why precision astrometry—the astronomical measurement of a star’s position, speed and direction of motion—will be needed to predict where a target star will be, and not where it currently is, when our future interstellar mission gets there.

To test this, we don’t need to wait until humanity has the means to build a starship, however. We have a bunch of interstellar probes that have already started their epic sojourns into the galaxy.

Interstellar Interlopers

Earlier this year, NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft departed the Sun’s sphere of influence and became humanity’s second interstellar mission, six years after its twin, Voyager 1, made history to become the first human-made object to drift into the space between the stars. Both Voyagers are still transmitting telemetry to this day, over 40 years since their launch. Another two spacecraft, the older Pioneer 10 and 11 missions, are also on their way to interstellar space, but they stopped transmitting decades ago. A newcomer, NASA’s New Horizons mission, will also become an interstellar mission in the future, but it has yet to finish its Kuiper belt explorations and still has fuel to make course corrections, so predictions of its stellar encounters will remain unknown for some time.

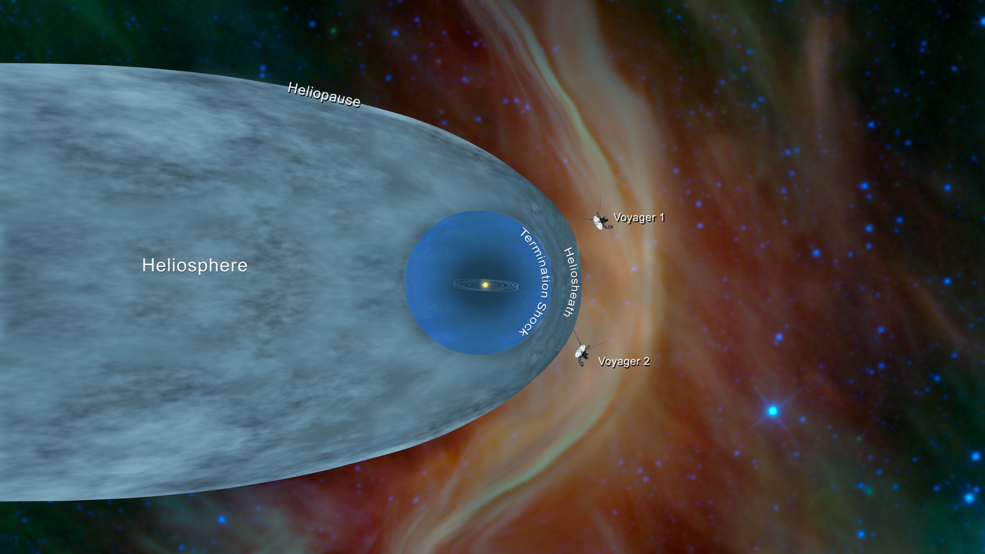

Having explored the outer planets in the 1970’s and 80’s, the Voyagers and Pioneers barreled on, revealing stunning science from the outer solar system. In the case of Voyager 1 and 2, when each breached the heliopause (the invisible boundary that demarks the limit of the Sun’s magnetic bubble, between the heliosphere and interstellar medium), they gave us a profound opportunity to experience this distant alien environment, using their dwindling number of instruments to measure particle counts and magnetic orientation.

But where are our intrepid interstellar interlopers going now? With the help of precision astrometry of local stars observed by the European Space Agency’s Gaia space telescope, two researchers have taken a peek into the future, seeing which star systems the spacecraft will drift past in the next few hundred thousand to millions of years.

Previously, astronomers have been able to combine the spacecrafts’ trajectory with stellar data to see which stars they will fly past, but in the wake of the Gaia Data Release 2 (GDR2) last year, an unprecedented trove of information has been made available for millions of stars in the local galaxy, providing the most precise “road map” yet of those stars the Voyagers and Pioneers will encounter.

“[Gaia has measured] the positions and space velocities of nearby stars more precisely than before and so has more precisely characterized the encounters with stars we already knew about,” says astronomer Coryn Bailer-Jones, of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany.

Close Encounters of the Voyager Kind

Bailer-Jones and colleague Davide Farnocchia of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., published their study in Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society, adding another layer of understanding about where our spacecraft, and the stars they’ll encounter, are going. Although their work confirms previous estimates of some stellar close encounters, Bailer-Jones tells Astroengine.com that there have been some surprises in their calculations—including encounters that have not been identified before.

For example, the star Gliese 445 (in the constellation of Camelopardalis, close to Polaris) is often quoted as being the closest encounter for Voyager 1, in approximately 40,000 years. But with the help of Gaia, which is giving an extra layer of precision for stars further afield, the researchers found that the spacecraft will come much closer to another star, called TYC 3135-52-1, in 302,700 years.

“Voyager 1 will pass just 0.30 parsecs [nearly one light-year] from that star and thus may penetrate its Oort cloud, if it has one,” he says.

This is interesting. Keep in mind that the Voyager and Pioneer spacecraft include the famous Golden Records and plaques (respectively), revealing the location, form, and culture of a civilization living on a planet called “Earth.” For an alien intelligence to stumble across one of our long-dead spacecraft in the distant future, the closer the stellar encounter the better (after all, the likelihood of stumbling across a tiny spacecraft in the vast interstellar expanse would be infinitesimally small). Passing within one light-year of TYC 3135-52-1 is still quite distant (for instance, we currently have no way of detecting something as dinky as a Voyager-size probe zooming through the solar system’s Oort Cloud), but who knows what the hypothetical aliens in TYC 3135-52-1 are capable of detecting from their home world?

Another interesting thought is that these Gaia observations can help astronomers find stars that are currently very far away, but now we know their speed and direction of travel, some of those stars will be in our cosmic backyard in the distant future.

“What our study also found, for the first time, is some stars that are currently quite distant from the Sun will nonetheless come very close to one of the spacecraft within the next few million years,” says Bailer-Jones. “For example, the star Gaia DR2 2091429484365218432 is currently 159.5 parsecs [520 light-years] from the Sun (and thus from Voyager 1), but Voyager 1 will pass within 0.39 parsecs [1.3 light-years] of it in 3.4 million years from now.”

In some cases, given unlimited time, you may not have to go to a star, the star will come to you!

Our Interstellar Future?

While pinpointing the various stellar encounters for our first interstellar probes is interesting, the observations being made by Gaia will be important for when humanity develops the technology to make a dedicated effort to travel to the stars.

“It will be essential to have extremely precise astrometry of any target star,” explains Bailer-Jones. “We must also measure its velocity and its acceleration precisely, because these affect where the star will be when the spacecraft arrives.”

Although this scenario may seem a long way off, any precision astrometry we do now will build our knowledge of the local stellar population and boost the “legacy value” of Gaia’s observations, he adds.

“Once a target star has been selected, we would want to make a dedicated campaign to measure its position and velocity even more precisely, but to determine the accelerations we need data measured at many time points over long periods (at least tens of years), so Gaia data will continue to be invaluable in the future,” Bailer-Jones concludes.

“Even now, astrometry from the previous Hipparcos mission—or even from surveys from decades ago or photometric plates 100 years ago!—are important for this.”

Update (May 23): One of the reasons why I focused on the Voyager missions and not the Pioneers is because the latter stopped transmitting a long time ago. Another reason is because we already know Pioneer 10 doesn’t make it very far into interstellar space:

For more on how Gaia observations are being used, see my previous interview with Coryn on how these data were used to find the possible origins of ‘Oumuamua, the interstellar comet.