It’s both too hot and too cold, has no atmosphere, and is no place to take a vacation—but there is an upside.

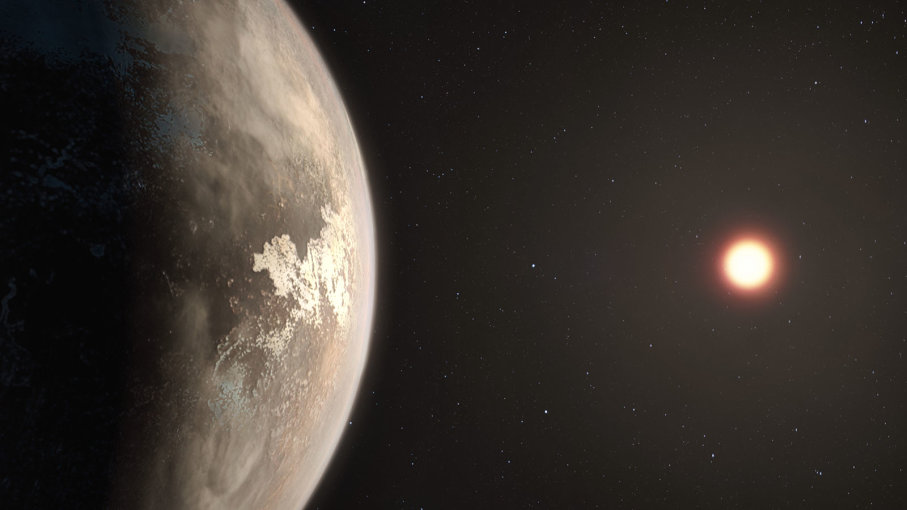

It’s hard to say anything positive about the exoplanet LHS 3844b. It’s a wretched place; an alien world that orbits its tiny star in less than half a day. As it’s so close to its red dwarf star, it’s tidally-locked—when one side of the planet is always in baking daylight, the other side is in a perpetual frozen night. Oh, and it doesn’t even have an atmosphere.

Why the heck am I even writing about this unfortunate celestial object?

Well, it might not be our idea of an interstellar getaway, but it is remarkable for two profound reasons: It’s a rare look at the surface conditions of a rocky exoplanet orbiting a distant star, and the very fact that astronomers are confident it doesn’t have an atmosphere is a really big deal.

World of Extremes

Discovered in 2018, LHS 3844b is located nearly 49 light-years away. It has a radius 30 percent larger than Earth and orbits a cool M dwarf star. It was detected by NASA’s newest space-based exoplanet hunter, the Transiting Exoplanet Satellite Survey (TESS); every 11 hours, the world drifts in front of the star, blocking a tiny amount of light (and event known as a “transit”) that can be detected by TESS. As it orbits so close to its host star, it’s glowing bright in infrared radiation, giving the researchers of a new study published in Nature an incredible opportunity.

Using observational data from NASA’s Spitzer space telescope, which views the universe in infrared wavelengths, and as the star is comparatively cool and dim, the researchers could discern how much infrared radiation was being emitted from the exoplanet’s “day” side and calculated that it must be cooking at a temperature of 1,410 degrees Fahrenheit (770 degrees Celsius). On measuring the infrared emissions from the exoplanet’s dark side, they realized that the heat from the day side wasn’t being transported to the night side. On Earth, our atmosphere distributes thermal energy around the globe, ensuring that the night and day sides’ temperature difference isn’t so extreme. LHS 3844b, however, isn’t distributing any of its thermal energy creating a sharp drop-off in temperature between both hemispheres. In other words: no atmosphere!

“The temperature contrast on this planet is about as big as it can possibly be,” said Laura Kreidberg, a researcher at the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and lead author of the new study. “That matches beautifully with our model of a bare rock with no atmosphere.

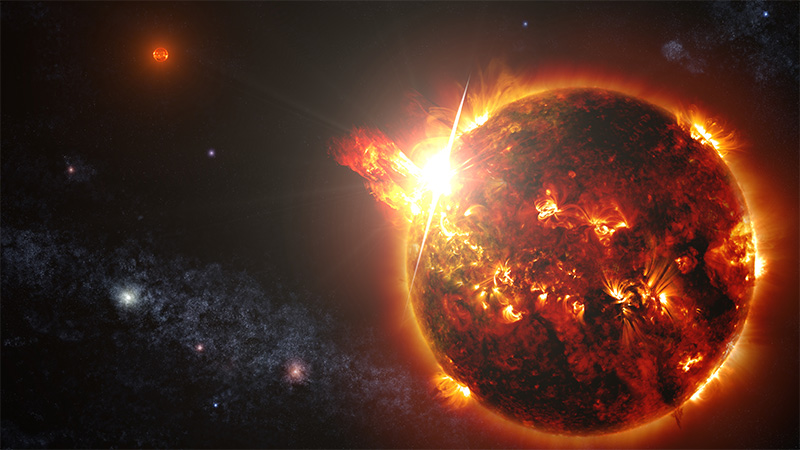

“We’ve got lots of theories about how planetary atmospheres fare around M dwarfs, but we haven’t been able to study them empirically. Now, with LHS 3844b, we have a terrestrial planet outside our solar system where for the first time we can determine observationally that an atmosphere is not present.”

This exoplanet has about as much atmosphere as the planet Mercury or our Moon, and it shares some other traits too. By measuring the amount of starlight the exoplanet reflects (a characteristic known as “albedo”), Kreidberg’s team also took a stab at understanding its composition.

As the world is “quite dark,” they deduced that it’s very likely that it’s covered in basalt (volcanic rock), the same stuff that we find in the crusts of the Moon and Mercury. “We know that the mare of the Moon are formed by ancient volcanism,” said Renyu Hu, an exoplanet scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., “and we postulate that this might be what has happened on this planet.”

An Atmospheric Problem

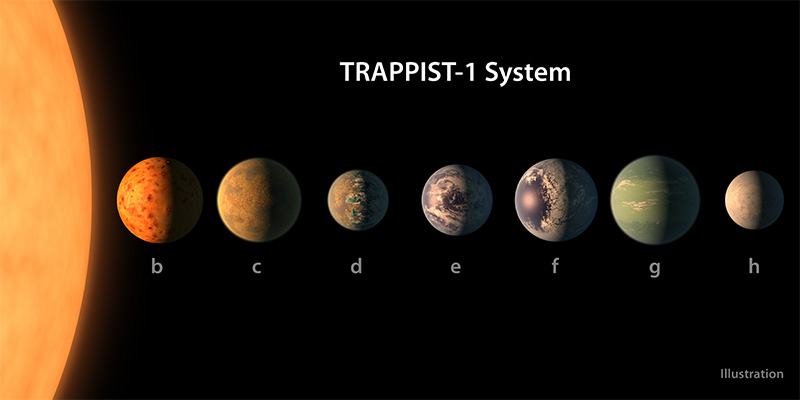

Red dwarfs are known to play host to entire systems of exoplanets, including many small rocky worlds of similar dimensions as Earth. Many of these worlds have been found within the much-hyped “habitable zone”, where it’s neither too hot or too cold for liquid water to persist. As we probably are all aware, liquid water is super helpful for life (on our planet, at least) to evolve. While LHS 3844b could never be considered “habitable” in any way, shape or form, the fact that it doesn’t have an atmosphere may be very revealing.

It’s simply not good enough to find a habitable zone exoplanet that orbits a red dwarf and say “there’s a good chance that aliens live there!” Even though it has the right temperature, because it’s orbiting a red dwarf and likely tidally-locked could mean these types of worlds are devoid of atmospheres, a serious wrench in the hope that all habitable zone exoplanets have the same likelihood of life. That’s not to say all red dwarf-orbiting exoplanets lack atmospheres, but now at least we are developing techniques that could, one day, help us from the atmospheric potential of more “habitable” candidates.