Earth likely passed through “a fold in the heliospheric current sheet,” which induced a powerful electrical surge down here on the ground.

While science news is filled with rumbling earthquakes and rippling gravitational waves, a different kind of perturbation was felt in Norway yesterday (Jan. 6)—but its cause is a little mysterious.

“Electrical currents started flowing,” said Rob Stammes, of the Polarlightcenter geophysical observatory in Lofoten, Norway, in a report by Spaceweather.com.

Stammes monitors the flow of electricity through the ground and compares it with the wiggles of the Earth’s magnetic field (as plotted above). These two key measurements allow space weather scientists to better understand how our planet’s magnetosphere is being affected by the magnetic field of our Sun and how it may impact our everyday lives.

While the Sun-Earth relationship is well studied, usually magnetospheric jiggles are associated with obvious (and often explosive) solar phenomena, such as coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and powerful solar wind flows. Yesterday, however, at around 1930 UT, our magnetosphere was jolted by a phantom event.

It was as if Earth orbited through an invisible magnetic speed bump.

Before we can understand what this means (and, indeed, why it’s important), let’s take a quick trip to the biggest magnetic dynamo in the Solar System.

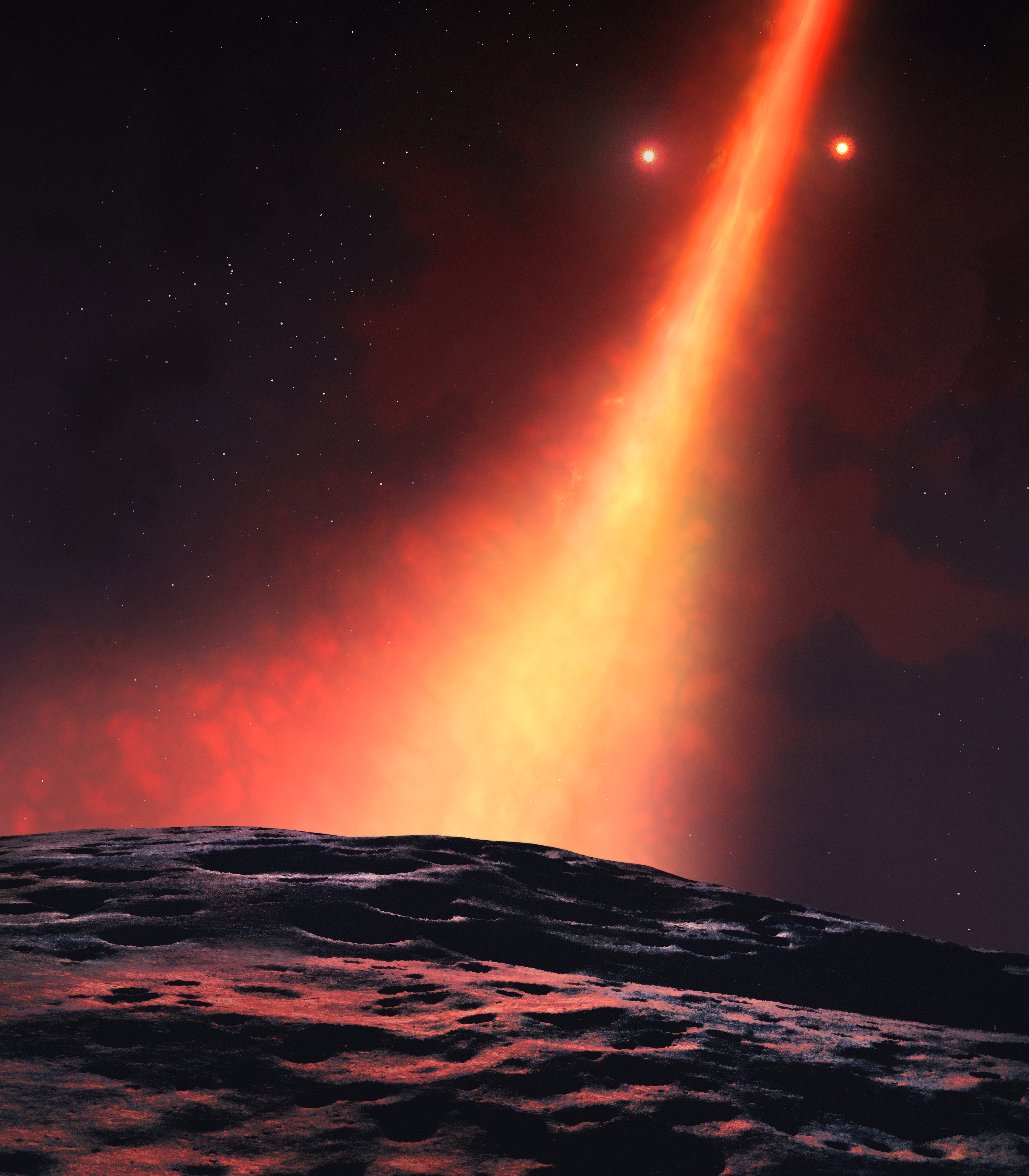

You know it as the giant orb of superheated plasma that gives life to Earth and dazzles you during your commute home from work, but the Sun also has an invisible magnetic dominance over all the planets. Extending from the solar interior to well beyond the orbit of Pluto, the Sun’s magnetic field creates a vast magnetic bubble called the heliosphere. Carried by the solar wind, this magnetism spirals out, through interplanetary space, interacting with any other magnetic field it may come across. In the case of our planet, our global magnetic field (the magnetosphere) is generated by the constant sloshing of molten iron in Earth’s core. Our magnetosphere reaches out into interplanetary space and, like a forcefield, it deflects the highly energetic plasma (consisting mainly of protons and some highly ionized particles) sloughing from our Sun. There’s a constant magnetic battle raging over our heads; the Sun’s magnetic field washes over our protective magnetosphere, which acts like a sea wall protecting the coastline from an unrelenting stormy ocean.

Now, if the conditions are right, the Sun’s magnetic field may breach Earth’s magnetosphere, causing the two to snap and reconnect, effectively creating a temporary magnetic marriage between the Sun and Earth. When this happens, a magnetic highway for solar particles is formed, injecting the layers of our magnetosphere with solar plasma. Ultimately, this plasma can stream along our planet’s magnetic field (or get trapped and stored), creating auroras in higher latitudes and generate electrical currents through the atmosphere and surface.

Usually, space weather forecasters use a plethora of instruments to predict when this might happen. For example, they may detect a CME erupt on the corona, predict its speed, and then register a flip in the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) by a satellite between us and the Sun (such as NASA’s Advanced Composition Explorer, or ACE, which is located at the Sun-Earth L1 point, nearly a million miles “upstream” toward the Sun). But, in the case of yesterday’s mysterious event in Norway, there was no warning for the magnetic breach in our magnetosphere. No CME, no visible increase in solar wind intensity; just a magnetic blip from ACE and a shockwave sent ripping through magnetometer stations on the ground followed by a surge in electricity through our planet’s surface.

We’d been suckerpunched by the Sun’s magnetism, but there was no obvious fist. To confirm the sudden magnetic blow (called a geomagnetic storm), magnificent auroras erupted over the poles.

So, what happened? There is a theory:

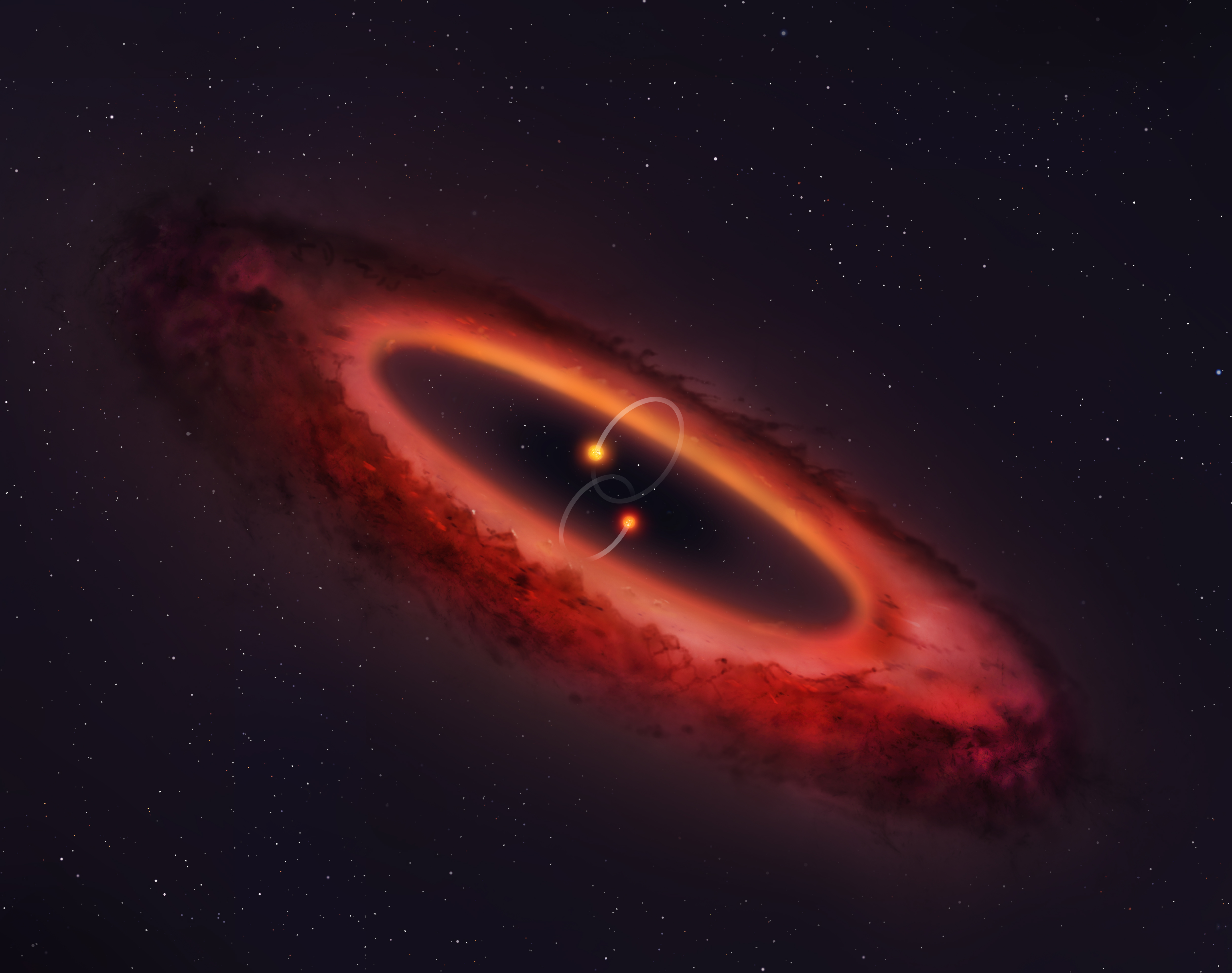

Earth may have crossed through a fold in the heliospheric current sheet—a giant, wavy membrane of electrical current rippling through the solar system. Such crossings can cause these kind of effects.

Tony Phillips, Spaceweather.com

Looking like the warped disk of an old vinyl record, the heliospheric current sheet ripples throughout the solar system. As Earth rotates around the Sun, it will pass through the “surface” of this sheet, where the magnetic polarity of the IMF will rapidly change. And this is probably what happened yesterday. As the Earth orbited through a fold in the sheet, the magnetic polarity flipped 180 degrees, creating the phantom interaction with our magnetosphere. This, in turn, released solar particles that had been trapped in the layers of our magnetosphere, causing them to surge through the upper atmosphere, creating an intense—and surprise—auroral display.

Predicting when these events are going to occur is critical to space weather prediction efforts. As demonstrated by Stammes’ measurements of currents flowing through the ground, geomagnetic storms can overload national power grids, leaving entire nations (or, potentially, entire continents) in the dark.

While this Norway event didn’t cause reported damage to any infrastructure, it is a reminder that our planet’s interactions with the solar magnetic field—and subsequent impacts to our civilization—can be unpredictable and, in this case, invisible.